As at the approach of Christmas the heart of every good Christian is filled with joyful anticipation, so too, the San Felipe and Santo Domingo Indians are similarly affected. Weeks and even months in advance they inquire how long it is until noche buena, the holy night, (literally the “goodnight”), conies and then in their own primitive fashion try to count again on their fingers the number of days.

True, the majority of these Indians might hardly grasp completely the real significance of this most beautiful of all feasts; still their tradition, though somewhat confused, tells them; that it must be a very great festival, wherefore corresponding preparations are made betimes.

Several days before Christmas they begin to set things in order and to bake, for though throughout the year they are often obliged to skimp, on this day there must be an abundance of bread, even Guayace, (a thin, paper-like Indian bread, of which they are very fond), or at least Biscoches (a confection) must be served. The little broom of hair grass too, otherwise used but rarely, is applied quite energetically during these days of preparation.

On the afternoon of December 24th, I left Peña Blanca in order to celebrate midnight Mass at San Felipe, 14 miles away. My way led through the Pueblo of Santo Domingo, inhabitated by 900 Indians where I noticed that not all the preparations for the morrow had been completed. Now and then dense clouds of smoke could be seen curling from semi-globular adobe ovens, a sign that baking was still in progress. Half a dozen elderly Indians, apparently city fathers, their weather-beaten faces carefully wrapped in woollen blankets, walked, silent and dignified, from house to house, to announce to each one the approaching salvation of the world. The leader of this embassy carried three or four feathers in his hand, which, had they had the color, might well have been mistaken for Palm branches. But somehow, feathers are pre-eminently chosen in all the ceremonial customs of these Indians. I called at the house of the sacristan, for in previous years he had accompanied me on this nightly tour. But as he was not at home, I made the journey alone. In fact, I did not need a guide. Since the Government has built a substantial bridge across the treacherous Rio Grande at San Felipe (thanks to the endeavors of Father Ketcham) it is not necessary to ford it any more.

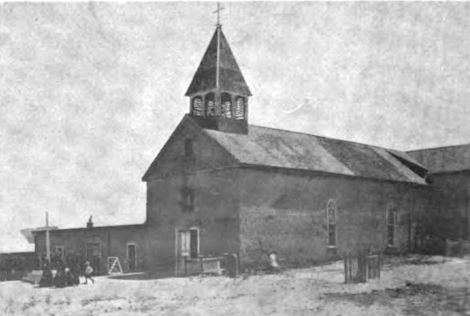

Church at Pena Blanca

It was rather late when I reached the Pueblo of San Felipe. The fiscal or church warden at whose house I stopped, and where some Indians had gathered, had already expressed to them his anxiety lest something had detained the Padre. But now they felt relieved and presently the dull sound of the old cracked church bell announced to all in the Pueblo that the tontoech was already in their midst. Supper was soon over. It was relished pretty well, for hunger is the best sauce.

After the Indians had rolled a few cigarettes and smoked them, I proposed to retire. Accompanied by a few natives. I repaired to the church building, in the rear of which a small room serves as my sleeping-place. On the way thither we passed a house, from which wailing sounds told of someone in great distress. We entered and beheld a pitiful sight hardly in keeping with Christmas joy, a picture of human misery. In the corner on the floor, lay a woman, wheezing and groaning her whole face covered with festering sores. Apparently, she was in danger and I hastened to perform my duty. As the patient spoke Spanish but very imperfectly and no English whatsoever, I prepared her with the aid of an interpreter as well as circumstances allowed. After administering Extreme Unction, I spoke a few words of consolation and encouragement and left her quiet and resigned. “Peace on earth to men of good will” the angels sang on this very night centuries ago, on the plains of Bethlehem. After staying a few minutes in the sacristy, where some Indians and a few Mexicans from surrounding villages were warming themselves at the fire-place, I prepared to retire. But first I explained to the fiscal where the hands of my watch would be, when it was time to wake me. Good night! God keep you ! and one, at least, was soon slumbering in the arms of Morpheus.

Church of Cochiti

At two o’clock there came a rap at the door and then the brazen-tongued bell, hoarse and broken, sought to arouse the sleepers. Things began to move lively in the village. The fiscal beating a drum accompanied by his aides, led the way through the village to call the Indians to Mass. It is their custom to have the pregoneros go from house to house to gather the congregation. The ringing of the church-bell is of no consequence.

I entered the church where I found the altar tastefully decorated. Before the altar the Indians had erected a hut of cedar twigs, covered with a roof of straw. Tufts of cotton batten were interspersed among the branches, which gave it a wintry appearance, ami, as it was bitterly cold; it seemed all the more real. One by one the Indians dropped in. Fextinalente “make haste slowly” applies especially to them. In about an hour, a goodly number had arrived. Wrapped in their blankets, they squatted on the floor. Of course, it could not be expected, that all would be present. The dancers must “prepare” themselves in order to dance before the crib immediately after Mass: but to do both, attend Mass and then dance impossible!

A dance! in Church! before the crib! What a scandal, a desecration, a sacrilege! someone might say. And the benches? Are they removed! Well there are no benches for, as I just mentioned, the Indians squat on the floor, which is not even a wood floor, but just Mother Earth. The interior of an Indian church is very bare, at least at San Felipe and Santo Domingo. Four adobe walls, whitewashed within, an .adobe roof, generally leaking in places, with an adobe floor: truly not unlike the stable of Bethlehem! A few simple boards nailed together to form the altar, a statue of St. Philip, a few mural paintings to serve as ornaments, and you have a complete Indian church.

To return to our Christmas celebration, I began Mass about 3 o’clock. At the sermon delivered in Spanish, I employed a reliable interpreter. Above all the fact was emphasized, that the same Infant Jesus, whose birth we were celebrating in that holy night, was really and truly present on the altar after elevation. No doubt, many an upright mind in my audience adored the Eucharistic Lord from the depths of his sold, and consecrated his heart to the Divine Infant. During the whole Mass all was quiet except for the flute players, who can faithfully imitate song birds.

After Mass an Indian woman took the statue of the Infant from the crib, placed it on her knee, and sat down upon a chair. A little boy stood beside her. Now all present, old and young passed before her, made their act of homage and offered a piece of bread. (This would prove a good supply for the sacristan, even though seven unfruitful years should set in). After this tribute of veneration, two divisions of dancers came marching in a motley group. Their heads were decorated with feathers interwoven with many colored ribbons; from their loins hung coyote or wildcat skins; beaded strings quavered on their wrists, tiny bells tinkled at their ankles, in their hand each held a dried, hollowed gourd in which small stones rattled at every motion.

Rigged out with these trappings, the dancers entered the church in single file, followed by the choir and the drummer who carried the huge tombe (a drum used by the Indians in their dances). Presently, they take their places in two rows, the tombe is beaten, the choir begins to chant, the dance is in full swing. Singly, yet uniformly they leap up and down to the harmonious beat of the drum and the rattling of the gourds. Their faces betray no emotion, for the dance is a sort of prayer with the Indians. It would lead too far to explain minutely even one of the 10 different dances performed by them. But you are cordially invited to see for yourself. Ample opportunity is offered you several times a year.

After the first division had thus shown its reverence to the Divine Infant, it withdrew to be relieved by the other one. Only the first dance is performed in the church by both divisions, the other dances are given on the plaza, an open place of the Pueblo, and kept up for four days.

Source: The Franciscan Missions of the Southwest, Published annually by the Franciscan Fathers at Saint Michaels, Arizona, 1917.